The Circle: A Film on the Experience of Being Incarcerated

October 14, 2021 - 10:00 am

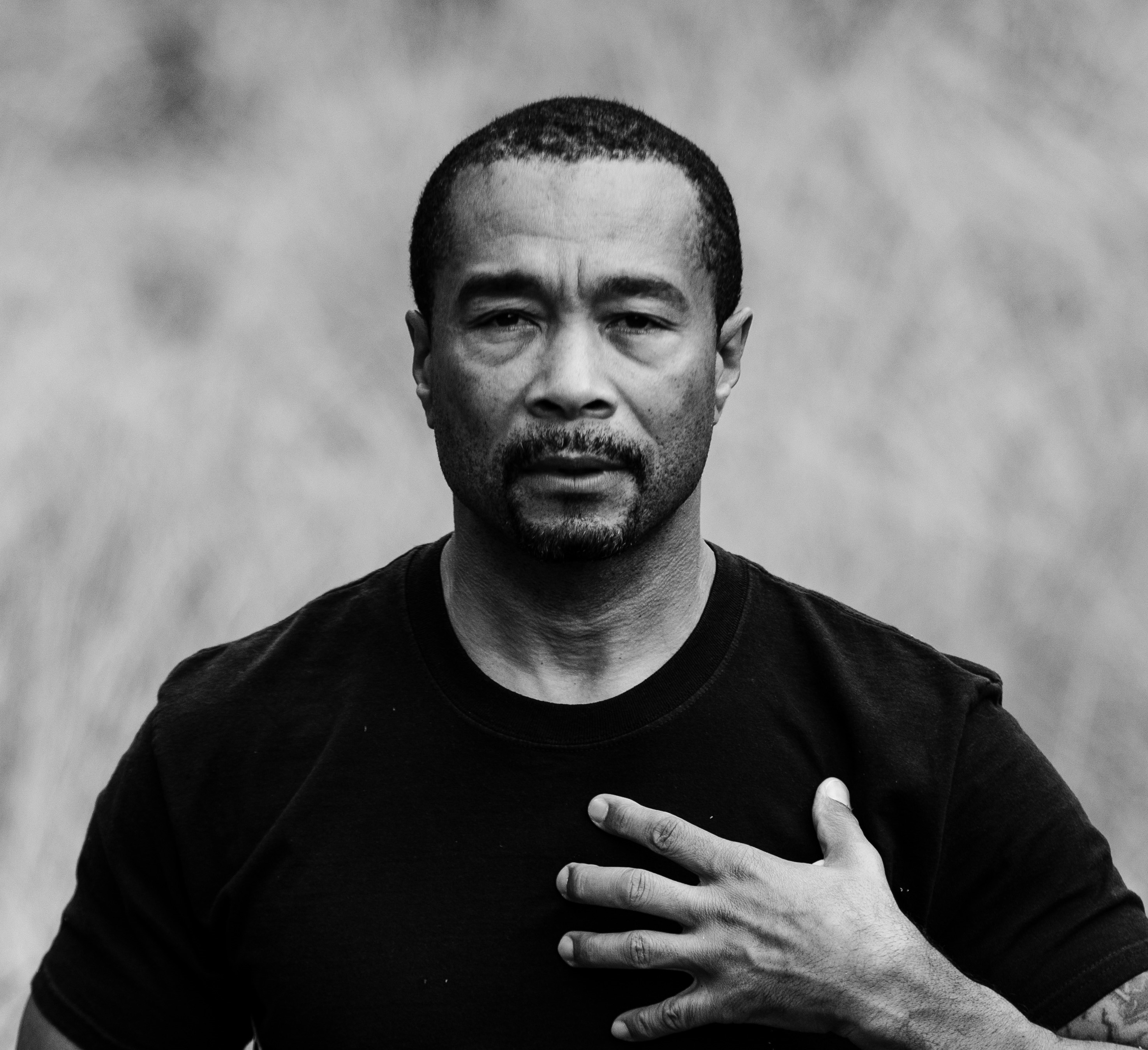

The Social Justice Film Festival is featuring The Circle, a film representing the artistic expression of people who are incarcerated. Two artists involved in this film, Allen Burnett and Marlene McCurtis spoke with KBCS about the genesis of the film and the lived experience behind it. The Circle can be viewed virtually through October 17th during the Social Justice Film FestivalProducer: Yuko Kodama

Photo: Marlene McCurtis

Y K 0:00

91.3 KBCS music and ideas. The Social Justice Film Festival is featuring ‘The Circle’ of film representing the artistic expression of life as someone who’s incarcerated. Two artists involved in this film, Alan Burnett and Marlene McCurtis, spoke with me last week about the process and people behind it. Here’s Burnett talking about what it’s like being on the inside. He spent 27 years behind bars on a life sentence until 2019, when California Governor Gavin Newsome commuted him

Alan Burnett 0:35

With people that are sentenced to life without the possibility of parole. We are like this separate class of a prison inmate, to where those programs are not readily available for us, because they feel like you’re never going to get out of prison. So therefore, that excluded us from certain jobs, from being able to participate in educational programs, to being able to participate in a lot of these self help programs that were available at institutions. – Which there wasn’t a lot.

Alan Burnett 1:04

I got arrested when I was 18, I was imprisoned by the time I was 20. So I grew up in prison. And I know like, I couldn’t do anything, I already had a high school diploma. But for some men, they weren’t even allowed to go to the GED class because of their sentence. And so what happens is, men and women began to develop this feeling of oppression. And they’re just walking around like zombies. And that’s what’s going on – just waiting to die. And the only joy that they find is things on television, getting a package, or receiving a visit, if they’re lucky that they still have someone to come and visit them. And that’s a huge problem, because these men and women are also the people who set the standard for what type of programs go on inside the prisons. There’s a ripple effect to that. So if you have men, who absolutely have no hope of ever getting out of prison, participating in these programs, it gives other individuals who have a shot at going home, whether through the parole board, or early release, or whatever it is – They say, well if these men are doing it, and this is the culture of the prison, that I should participate in that. Because ultimately, these men are going to be the ones that are going to come home. So if they’re in an environment, where there’s consistent violence, drug abuse, lack of communication, no conflict resolution, – They’re going to take that same behavior back out into the community, they always say that prisoners who have lives without are the least likely to cause problems, because of the sentence like, after a while, like you get it. ‘I’m in here forever, like I don’t even want to get in any trouble. I would rather do things to help people.’

Alan Burnett 2:40

I was fortunate enough to be around men who were similarly situated as myself, who were writing books, who were teaching classes, who were working in administration office, who were helping other individuals. That, for me was normal. And I was able to step into that space and thrive in that space. Those programs are absolutely needed. That’s part of the reason why I’m home today, like part of the work that I’m doing now in the community is helping to create these programs, because California has multiple prisons. And then there’s places where men haven’t even found out or took the time, or had the opportunity to understand how they developed into a person who can commit a crime. – How they can take another human beings life. The men that I’ve been fortunate enough to meet have had the most worst experiences. You have men who were molested from the age of six to 16, who murdered their molester, a good friend of mine, his father, shot his mother and then turned a gun on himself, he came and found his parents in the bathroom like that. So he grew up, and this is the person he developed into where we can commit this crime. And the beauty about the programs is, it helps a person ‘say wait a minute, my parents arguing and fighting, that’s not normal. That’s domestic violence. My parents, my father, drinking and doing I was affected by drug and alcohol abuse. Me being molested is something that happened to me as a child, I shouldn’t be ashamed of it as a man when he developed his toxic masculinity to I need to be super aggressive towards men’. And some men hate women, because of these things, but they haven’t had the opportunity to figure this out, because they haven’t had the programs and the resources to do it.

Alan Burnett 4:20

And so as a society, we want our society to be safe. There has to be a connection between the people that are incarcerated, and the people who aren’t incarcerated. And these things need to start getting fixed, not on the back end, after someone commits a crime. We’re going to lock him up. He deserves to die in prison. That was a horrible thing that he did, he shouldn’t have killed that person. When the things should be we need to figure out what is going on in our households. And what we teach our young people in school to help them develop into people so they know that they have other options as opposed to taking another human beings life. So this is the this is how I developed throughout my incarceration.

Alan Burnett 4:58

I’m so thankful that I had The last 10 years of my prison sentence, I spent it at the progressive program and facility where all these things were like available. And what’s interesting when I say they were available, the administration wasn’t the ones who provided it for us. It was the man who were there saying, you know what, this is something that we need, we’ll create these programs.

Alan Burnett 5:20

The progressive programming facility was started by former man serving life without the possibility of parole and Kenneth E. Hartmann. And he wrote a proposal. And in the proposal, we said, we want to have a yard, a facility for buildings, five buildings where there’s no drug and alcohol. And these men are, there’s no racism and all these things. And if a person who’s incarcerated, participate, they would sign a contract. And that was in 2000. And it was called the honor yard. And then it went through all this political ramifications and they changed it to the progressive programming facility and it developed. And so now there’s a dog program there. There’s a Bachelors of Arts degree with in-person staff come there and teach these type of programs.

Alan Burnett 6:04

In 2017 to 2020, former Governor Brown and Governor Newsome began to commute sentences of the men that were housed on that facility, because of the tremendous amount of work that they were doing and the social impact it was having in the community. We started the programs. I myself, started a couple programs while I was in that facility, and they benefited so many people, not just men serving life without, but other men to give them the understanding of who they are so they can become better people.

Y K 6:36

The film ‘The Circle’ now showing at the social justice Film Festival was created by people incarcerated at the California State Prison, Los Angeles County, Lancaster. Artists, Marlene McCurtis and Susie Tanner were the working artists. And when the pandemic hit the work took to film here, McCurtis describes the project.

Marlene McCurtis 6:59

What our workshops are, is that we come in, we do writing exercises, we do movement, we do theater, all in preparation for a final performance, which the men write and also perform. However, COVID hit and we were shut down, we thought for only two weeks. And obviously that changed. And we had to kind of figure out what we were going to do.

Marlene McCurtis 7:22

Thank goodness, we’re funded by arts and corrections, which is under the California Arts Council. And we worked with the prisons and CDCR to do correspondence classes. So we were able to have those same men who were in that workshop continue writing through a correspondence course. But now we had this writing, and we were like, what are we going to do? I mean, how do we get their words out into the public, it’s so important to change the narrative and really show the humanity and the story of the men that are incarcerated. So it’s really kind of out of necessity. This came about and to submit, couldn’t say their words themselves.

Marlene McCurtis 8:05

During this time period to the men we worked with Alan Burnett and Louis brash, actually were released, so they were home. And we also had other men that we had worked with through re-entry programs through Theatre Workers Project. We decided that perhaps we would be able to have these men say the words of the men inside and be the performers, they were the actosr. So that’s what we did. And we filmed this during the pandemic. So a lot of it’s on zoom. And then some of it we work with movement person, Alexa Kushner, and we took the men into outdoor spaces and had them do movement, along with the recorded voices. And we blended that to make a film.

Marlene McCurtis 8:53

We wanted to get these men’s words, their voices out there. And luckily, as a teaching artist, I’m also filmmaker. So I was able to kind of step into that role, and help make that happen. And we were really very fortunate that we had these amazing men who were on the outside that were willing to kind of step in, and also be a part of this process.

Y K 9:19

Could you tell me if there’s like a particular moment when something happened and it ..it affected the way you look at things?

Unknown Speaker 9:28

I just have these like images in my mind of sitting down in front of young men who really reminded me of my sons and asking them the question, and I remember sitting – I just got this kid must have been – He may have been 18. And he was looking at 25 to live as we were going into jails. So he hadn’t been sentenced yet. And I remember talking to him, and I would always ask them, tell me about what your grades were like when you were like in second grade, third grade fourth grade. And he was like, Yeah, I was an A student. You know, I was actually on the football team in high school. And you know, he was just telling me all of this stuff about his life. And I guess for me, I always, you know, I always kind of feel like, Why Did anyone see you? Why didn’t anyone see who you were? I mean, you know, saw, you know that you were smart kid that you were an athlete. You know, my sons were smart, and they were athletes. Why didn’t anyone see you? Why didn’t you want this grab you up, and make sure that you are okay. And I felt that for so many of those young men. The first couple of years, I would like interview all these men and then I would get on the plane flying back to LA and literally would be in tears, like crying on the plane, like kind of like, you know, just replaying what I heard just the humanity of everyone I met. I mean, they’re human beings that are behind bars. I think we can’t forget about that.

Y K 11:05

Artist Alan Burnett now works for Theater Workers Project. Burnett had been serving a life sentence at California State Prison Los Angeles County, Lancaster. He participated in McCurtis and Tanner’s workshop while inside, since he was commuted, he teamed up with Mike Curtis to work on the film involving many of his friends from inside. Here, Burnett describes how serving a life sentence affects your experience inside the prison system.

Alan Burnett 11:35

First became involved with theater workers project when they started to come inside the institution. From 2010 to 2020, I was at this particular prison, which is CSP Los Angeles County. We call it the progressive programming facility. And at that facility, there were at the time, like hundreds of men serving life without parole, – well sentenced to death by incarceration. And while we were there, these men had started to create programs that dealt with domestic violence, criminals and gangs anonymous, victim’s impact. And so we already had this culture of rehabilitation, even though that we knew we would never get out of prison, we made a conscious decision to create programs and try to like become better people.

Alan Burnett 12:32

When theater workers project was introduced to our facility, it was something new, like we were just accustomed to going in a classroom, and just having these conversations and really unpacking our lives. But when there was an opportunity to do some, you know, some type of physical movement, and some theatrical work, like I said, why not. And so I signed up. And so that’s how I got involved, I just signed up on the list and came in, and I just wanted to see what it was about, it was probably one of the best decisions that I made, you know, while I was incarcerated.

Alan Burnett 13:04

They gave me a different platform to be able to express myself, like I could write, and I can stand up in class and talk about, you know, all the things that happened to me, that allow me to develop into a person that can make terrible decisions. But doing it, inthat space was completely different. I really had to, like, physically act out some things. And at one point, it was healing for me, you know, and it was also like, I saw the power to do that with my peers. And so while we were in that process together, we were also learning about each other. And it just created like this different type of bond than we had before.

Alan Burnett 13:45

I’m going to talk about my mom a little bit like my mother passed away. And, you know, I could express verbally, like how that felt, you know, but being able to take my body and show that range of emotions through the physical act of the performance piece. It was hard, but then I felt better. Because I was like, I needed to hug like, I needed somebody to love me, somebody to say it’s going to be okay, something that I wasn’t able to get in the classroom setting, or going to talk to the chaplain, because, like those are really strong emotions. And so doing it in like in that space, it helped me cope a little bit more. And while we were doing that, we also learned that not just myself but other men that were in the group were experiencing similar things. So you can see that this things manifesting.

Y K 14:37

What did that look like

Unknown Speaker 14:40

So first, obviously, like it’s super hard to lose a parent. I don’t care how old you are. You lose a parent that’s like that’s one of the most devastating feelings that our parents especially our mothers are our first love. We know their voice before we even see their face. And like so from day one that’s our first love. But to be incarcerated, and feeling helpless, and, you know, not being able to in jails and prisons or places where you really don’t show those type of vulnerabilities, because people tend to shy away, or they’re looking at it as a weakness. So you had to sit with that.

Alan Burnett 15:20

My mother had a stroke. And while she was going through her recovery, like I, I was fortunate to be able to ask an officer, if he would allow me to use the phone, at six in the morning, the phones generally don’t come on till nine o’clock, but he was understanding of my situation. So every morning at six o’clock, I would go down and use the phone. And I would just talk to my mom, and she could barely talk. And I would read scriptures to her. And everyone knew, like at that time, just to stay away from that area, because they knew I was out there, spending that time with my mother. And slowly she began to recover. And then she had a second stroke, and my mother was brain dead. and so, something broke inside of me. And I wasn’t able to talk, I lost a tremendous amount of weight, I was very depressed. And people would say things that they felt were helping me. But they weren’t like, well, she’s in a better place, or, you know, this is something that God wanted, or I had a guy who can tell me if he would have just prayed a little bit more, maybe she would still be alive. So I had all these different narratives going on in my head. And I was really hurt. And so what can I say? Like, how can I get people to understand this pain who’s never experienced it? And I don’t think anybody can. You’re not qualified to talk about what it feels like to lose a parent, especially my parent. And so when we had an opportunity to participate in this particular program, I began to think about, like, what my feelings were, how did I manifest those feelings? Like how can I bring those feelings to life, and express them in a way that I wasn’t able to do verbally.

Alan Burnett 17:04

I remember there and I would sign up for the phone. When my mother passed away, I still would go down there and get on the phone at six o’clock and dial a number. And so I wanted people to understand what that felt like for me. And so my performance was about me going and using that phone, and dialing and dialing and dialing and dialing. And then people really, and then they got it, because she was not gonna answer the phone. but on so many levels. It also allowed me to reflect on the amount of pain and suffering that are caused with my life chronic. And so I had these two things run in parallel. On one hand, it was it was healing. And another hand, it was a realization like, this is what it feels like to truly lose someone that you love, and feel helpless about it.

Alan Burnett 18:01

I’m extremely thankful for the timing of theatreworkers project coming into the institution. And me having the courage to go in and sign up and express myself that way. Because it helped me. In prison, there is no will let you go to the funeral. Or you can watch the funeral from an electronic device or the chaplain told me you’ll be okay, just continue to pray. Like they were just uncaring because there was nothing set in place to deal with these range of emotions that inmates or prisoners experience. And so how do I process that like some people commit suicide, some people go to drugs and alcohol, some people start to get involved in this destructive behavior, because they haven’t completely processed that. And so theater workers project allow me to process it in a healthy way.

Alan Burnett 19:01

When I came to prison, which was 1994, the only programs that they had were like, Alcoholics Anonymous, in Narcotics Anonymous. And those were generally held on the weekends for a couple hours a day. And then the institution housed eight buildings on the facility. And so then there wasn’t this culture of rehabilitation, because the men knew that they weren’t going to get out of prison. So what was the point even going to the classrooms?

Alan Burnett 19:32

We had a governor at the time, it was Pete Wilson. And Pete Wilson was saying that the only way that he would let someone out of a prison would be in a pine box. let me say this, the first time I’ve seen somebody get out of prison was in 2011. And I came to prison in 1994. And so our system was geared towards punishment, lock them up. I think from the time that I did I came to prison. They began to erect all these prisons. We had , like 30 some odd prisons in California. By the time I paroled by the time I came home, and the prison system got so overcrowded with mass incarceration, they began to shift people out of state, Arizona, Mississippi, people were sleeping, triple bunks and sleeping on the floor in a prison. Like this is supposed to be America, like, what are we doing?

Alan Burnett 20:23

In 1994, the three strikes law was implemented in California. And so that just… they were locking -A lot of people were being sentenced to 25 years to life. And for the smallest thing, so that was pretty much like what blew up the prison system in terms of like mass incarceration, and then it just was like, boom. prison industrial complex, prisons everywhere, personal people own prisons. Then you had all these smaller companies that were invested in, you know, providing services for prisons, like packages, telephone services. And so they began to put more money into really more prisons. So it just became this big thing where everyone was making money off prisons. And let me just say this, too, there wasn’t a lot of like, programs like Theater workers project coming inside at the time, like that was unheard of like you never saw that. And then it got to a point to where now it’s a lot more nonprofit organizations, community based organizations that are now taking an interest into helping people that are incarcerated. Some of them are, you know, really good programs that really want to help. And some of them are following that same pattern. So this is a way we can get some money. It was really this telephone crime thing that was going on, like it was popularizing. While I was in prison, there used to be like plants and stuff, like they dug them all up, there was a thing called the prisoners Bill of Rights, which was scaled back around that time. And so prison became a place that was not just where we were isolated from the rest of society. But we were absolutely like cut off to where you couldn’t communicate, there was a time where a prisoner would be able to go and spend a couple of nights with his family, inside the institution, all that stuff was taken away, especially if you had life without parole. And so like, we became this story about this is where we send the bad people. And then we didn’t have a voice to where we can say, well wait a minute, like, I know, I’ve committed some terrible crime, I’ve changed and let me show you my humanity. So that was going on for many, many years.

Alan Burnett 22:36

Fortunately, there was a change. But I don’t know if you can imagine, like, we were just like, stranded somewhere, like on an island. And we couldn’t get any help. And so we began to, like, really just sit in that and start to believe that we weren’t worthy. At least I was, I felt like I wasn’t even worthy of having a conversation and talking about anything that was personal to me, because my sentence defined everything about me. And it was reinforced by the things that were being taken away from me, and the places where I was being sent, and it was reinforced by the activities that were going on around me. And so I just created this, this whole social construct about what it meant to have a life sentence and and be stuck in prison. And so you know, men will find a way out whether it was through suicide, or just numbing the pain by drug and alcohol abuse, and just repeating acts of violence. And so there was this really terrible cycle for many years. And we would be sent from prison to prison like, herded here, there here, there here, there. And that was going on for about 10 years. For me. Three strikes had a huge impact on the prison system, at least when I got there.

Y K 23:47

And you witnessed that shift from when you first got in. And during your sentence, when

Unknown Speaker 23:55

I first was arrested, I was 18. And like I said, in, in the end of 1994, I was in prison. And I was 20 at the time. And so there was opportunities that I would hear about these things. Like they’re like unicorns like, Oh, yeah, you can go get sent to a place where you can get programs and, you know, but if you got left out, it didn’t really matter. But then I started to see like the decline, there was more riots, more racial things going on. The food was scaled back. The exercise equipment was scaled back, and then it was just removed from the facility. And I mean, like, weights, there was no education programs, the trades, the vocational trades was scaled back. A lot of things were cut in those like, why did they even need it in the first place? Like what do they need that for these people deserve- They deserve to be locked up. I think the most devastating thing for me was, I remember I was in my cell in New Folsom. It’s a prison in Sacramento. It’s like one of the worst place you can send a kid. Don’t get me wrong. I’m not trying to minimize the fact that I I committed a crime. But it’s one of the worst places where you can send a 20 year old. And while I was there, I was watching the news. And there was this discussion about whether or not to take the family visits. And one of the prisoners, their mother who was like seven years old. And she was on the news that she says, the family business aren’t just for the husbands and the wives. It’s for the mothers too, My son’s been in prison. And this is the only time I get to spend with him because I can’t travel, you know, while I’m still alive. And immediately after that, which it felt to me, me, more media inside institutions.

Alan Burnett 25:37

So I never saw anything unless it was a riot. And then they would show the aftermath of the riot. And then the perspective of what these inmates were trying to kill these inmates and this inmate was shot. And by the way, this inmate was serving a life sentence. And he was a part of a gang. So the narrative that was being told, just reinforced the public’s idea of who they had incarcerated and why we needed to be there. At the end of the day, like, this is what I want. I would love for people just to understand that there is a connection, that this narrative needs to shift, there needs to be a huge shift about the men and women who are incarcerated, like our understanding of the justice system is unjust.

Y K 26:16

People were ending up with 25 year and more sentences for the smallest things. I mean, what are we talking about here?

Unknown Speaker 26:25

So there was a so I was in trial in 1994. And then you would have, I remember just a, influx of people they were coming in, they were arrested for things like this one individual who I was on the bus with, when I was going to new Folsom, he stole some meat from the grocery store. And he was arrested. And he was sentenced to 25 years to life. One of my roommates had some fake IDs. And he got three strikes plus enhancements, and he had a 55 years to life. And so there’s still men incarcerated right now from 1994. for crimes that are of that magnitude, who eventually that they may never get out of prison because of three strikes, whether health or whatnot. And then when the pandemic…, oh, that’s a whole nother thing. But the pen that I lost, like people that I really cared about, due to the pandemic, who had three strikes. One man in particular, his name was Terry Don Evans. And he had three strikes, I don’t remember exactly what his crime was for, but he was a part of my college cohort on the inside. And he died because of COVID. So a lot of people lost their lives while incarcerated for three strikes and whatever the case may be. But more to your point, Crime is crime, harm is harm. But 25 years to life is stealing me for having a fake IDs, 55 years to life, like it doesn’t doesn’t match. It doesn’t match. But

Alan Burnett 27:58

The three strikes law , it just became this thing, because there was an individual who had been in prison before, multiple times. And then what he did was, he committed an egregious crime. What happened with that was they said, Well, you know what, this man should have never even been out of prison, he’s a career criminal. If he wouldn’t have been out of prison, he wouldn’t have committed this crime. So now the public is like, Oh, my God, I can’t believe this happened. This man kidnapped this child, and he did this terrible thing. And he should have never got out. So now it’s like, it was the right time for a law like three strikes to come into effect, because everyone was pissed off about what happened. They were outraged. And in doing so, the law was so broad that if a person that had been incarcerated before he committed a crime, whether it was violent or nonviolent, they were getting 25 years to life as a result. So it was the reaction to a harm that another individual had cost, to have 25 years to live for three strikes for possession of drugs or drug paraphernalia, because you’ve been in prison before you have priors for drug, drug abuse and drug offenses, and you have a violent crime. Some men had went to California Youth authority when they were 1516 years old. And then like in their 30s, or their late 20s. They committed drunk driving, and then they got enhancements under the three strikes law, and then they have a life sentence.

Alan Burnett 29:26

My personal opinion is that we need to deal with these issues before they even get to that point. And I believe it starts with what we teach our young people in school, from K through 12. From 12 to master’s program, we need to be learning these type of lessons, cognitive behavioral therapy, relationship building, and just making just good decisions. Now that I’m home, I work with Human Rights Watch in the Children’s Rights Division, to bring awareness to life without the possibility of parole. It’s a nationwide campaign. And I also work with parole justice works, which we’re helping to create content for parole board attorneys, for survivors of crime, and for incarcerated men and women to help them understand how they got to a place where this was a viable option for someone to harm another human being. How did this happen?

Alan Burnett 30:20

All this work is just the embodiment of who I am now. And who I was while I was incarcerated. For me, it’s about how am I able to humanize myself and humanize these men and women who are called monsters. So I take the work very personal. I love these men, I love these women that I’m meeting now who are serving a sentence and sowhen I have an opportunity to share those words like, I need to jump in there and do it immediately.

Y K 30:49

just curious, what does it feel like going back in, in this way.

Alan Burnett 30:54

When we talking about connection, there is definitely like a disconnect between people who are formerly incarcerated and the rest of society, I feel more connected to the men and the women who have shared similar experiences with me, because we speak the same language. We come from a different culture now. And so when I go in, I was super happy to see my friends, I can say they’re my family. And when I talk to them, I’m able to express like, how I’m feeling and they understand. Because this is the impact of my incarceration. I still carry around this disconnect, where, though I may be able to exist in society and go places and do things, no one can ever really fully understand what it feels like to be in that setting, to be oppressed, to suffer, and then to develop.

Alan Burnett 31:53

You know, it just took me a minute, but I’m starting to realize that now, my friends, they call me, they want to know what I’m eating. They want to know, like, what the traffic looks like, what do I see, and they’re living vicariously through a 15 minute phone call. So being able to go in and embrace them. And just, you know, tell them that I love them. And I’m praying for them and hoping the same thing that I got, and I’m fighting for them.

Alan Burnett 32:24

The feeling of hopelessness is so thick, even when men are doing positive things , ultimately, life without parole means exactly what that is. It’s death by incarceration. And me getting my sentence commuted wasn’t a right. It was a gift. It was an acknowledgment. And it was one thing that the governor had the power to do. And he saw something in the work that I had done throughout my incarceration, and through my life of crime. The mitigating factors said, this person right here is worthy of an opportunity to go to the parole board and see if their rehabilitation is real for this individual. And so unless a person, a man or woman receives that, who served life without, they’re going to die in prison. And so just the understanding of that, and I see the faces and the expression of hopelessness, and then the hope.

Alan Burnett 33:19

You know, when I’m interacting with the men, I told him one individually yesterday, you getting ready for the parole board, and he almost fell out. He was like, Oh, my God, like, you think I got a shot? I said everyone has an opportunity coming, you just have to act like it’s gonna actually come and start preparing now. Learn to swim, because the boat’s coming in as you can swim from the land to the ship, you’re going to drown.

Y K 33:45

Marlene McCurtis. And Alan Burnett described the throughline of the film connection,

Marlene McCurtis 33:52

This idea that we’ve decided that we’re going to put a certain group of people behind these bars behind these walls, and we’re going to forget about them. And in fact, this piece is about connecting- knocking down those walls and making this circle inclusive and inviting you into this circle of humanity.

Alan Burnett 34:13

For me, when I observe the peace, it puts me in a place that I am connected to these men in these stories. And now look at us, we’re here having this conversation, there’s a connection going on between you and I. And when the viewers hear this, then they’ll realize that there is a bigger connection. locking people up doesn’t make us safer, but connecting each other, all of us being connected and understanding that in order for us to live and to exist, we are connected and separating ourselves, it isolates us and it doesn’t help us, It only hinders us. Like what they say if California sneezes the rest of the country catches a cold? That’s kind of like similar to like, if you like a person though. Are you helping society as a whole? Are you healing anyone? Are you making things better? You’re Not. Ultimately it is about connection. It is about the human spirit, it’s about us, realizing that we’re a people, in order for us to thrive, we need to love each other as opposed to like, these people are no good, they need to go die. It doesn’t help us, (It) doesn’t help anybody.

Y K 35:18

The circle is not a narrative film. But an adaptation of the written work of incarcerated people, read and performed with movement by people who have transitioned outside. like Burnett, McCurtis describes her personal experiences from the artistic process.

Marlene McCurtis 35:37

The thing about teaching inside is it’s not really that much different than teaching anywhere. I mean, these are students. they have a story to tell. I have a skill, and I’m bringing that skill into this environment. So I think we almost forget that we’re in prison. And that’s what we hope. Being a deep listener and listening to the men and they, you know, them teaching me as well about what works. I think the thing that is different is that the men we work with are very appreciative. So like, the first time I came into Lancaster to work, it was you know, every man that came in, walked up, introduced themselves. ‘Hi, how are you?’ And when we laughed, and this was like a ritual, everyone would come up, shake our hands. ‘Thank you’. So there is this level of humanity and appreciation that is so deep, and just beautiful, I think going into prison makes me a better person.

Y K 36:34

Are there certain phrases that are part of the film that that you want to share that hit home for you?

Marlene McCurtis 36:42

This is the last piece that is in the film. I don’t remember who wrote it inside. It’s ‘I feel accepted and welcomed. My whole being is nourished and healed from the embrace, I see nothing but feel everything. I stand taller now that I have shed my armor, my facade. This is truly who I am imperfect vulnerable’. I think this idea of shedding my arm or my facade – I think that that is a statement that for us on the outside, all of us to be vulnerable – to drop our facade and being imperfect to acknowledge that that’s difficult for anyone. And just imagine the bravery that it takes for someone who’s incarcerated, to be able to say that, and I would say that that is really, in many ways the power of art.

Y K 37:43

‘The Circle’ can be screened online streaming through the Social Justice Film Festival. More information is at socialjusticefilminstitute.org. For more KBCS stories and to support our work with a donation, you can visit KBCS.fm