Japanese American Elders Protest the Northwest Detention Center

Japanese American elders, their children and grandchildren, and many others held a protest at the Northwest Detention Center on Sunday, February 23rd. It was a partnership between Tsuru for Solidarity, Densho, Seattle Japanese American Citizens League and La Resistencia. This story looks at the generational impact incarceration has on families.

Tsuru for Solidarity is preparing for a pilgrimage on Washington DC from June 5 -7.

Full Story:

Many protesters gathered at Tacoma’s Northwest Detention Center, one of the largest ICE detention facilities in the nation. KBCS’ Sam Britt was there in heavy rain, and brings you this story.

I’m here at Tsuru for Solidarity’s Day of Remembrance and Action outside the Northwest Detention Center.

Despite the rain and the wind, before long, the streets outside of the Northwest detention center were flooded with people. huddled under umbrellas and tents surrounding the stage. Protesters activist and concerned citizens waited patiently for the events to formally begin. The crowd is filled with Japanese American elders that once faced incarceration by the United States, as well as the children and families of migrants that today face deportation or incarceration at facilities like the one here in Tacoma NW DC is one of the largest immigrant detention facilities in the country, owned and operated by the for profit corporation GEO Group. Inside, more than 1400 undocumented immigrants are housed, many of them for an undetermined period of time. The Japanese American group Tsuru for Solidarity organize the event today to protest the separation and incarceration of migrant families – something the Japanese community in the United States bears painful memories of.

James Arima: “I was born surrounded by barbed wire and guard cars in Crystal City, Texas. My father was separated from my mother and older siblings for almost three years. And I’m a product of the reunion. You know, and uh… I know that my father never recovered emotionally or economically from what was done to him. And my older siblings, people their age have memories of being incarcerated, but they claim they don’t. And I think it… it comes out in other ways from their suppressed memories. You don’t find them at events like this. I’m hopeful that someday they will because for many attending events like this it’s a healing.”

That’s James Arima, a survivor of the Japanese internment camps. He shared with me the lasting effects, discrimination and mass incarceration have had on him, his family and his generation growing up post World War Two. Dr. Satsuki. Ina is a Psychotherapist and founding member of Tsuru For Solidarity. She’s also a survivor of internment herself, and has devoted her life to studying the generational trauma her community still suffers with.

Can you describe to me your work and what you’ve discovered about group trauma,

Satsuki Ina: “Right. So, you know, collective historic trauma is something that has been inflicted on multiple groups of people of color in America. And particularly, my concern has been about children who are in this constant state of fear, separation, incarceration themselves, that when the nervous system and the brain is developing, to be in that state, actually alters physiologically, the brain functioning – so the child then grows up with a lot of anxiety and easily triggered defensive responses because of that. It’s influenced by culture too, so in my community, lots of anxiety and depression.”

And group trauma can touch more than just those who experienced the traumatic event. Its effects can be seen for generations to come. Mike, Ishii is a spoken word artist, and another founder of Tsuru For Solidarity, and the son of parents who went through the horrors of incarceration.

Mike Ishii: “What is confusing for us who were not incarcerated, but our descendants, is that we feel the trauma that was passed down through our parents to us. – and yet, it’s not happening, so you don’t understand why you have terrible anxiety, why you have panic attacks, why you lack confidence, why you feel so driven to have to do things perfectly, because after the war when they tried to come back into society, my family was targeted with violence. They shot our windows out, they spray painted death threats in front of the house. They would wait till my father left for work and they would call my mother and say, j*^ b#*@*, We’re going to come kill you now,”

And who was they?

Mike Ishi: “Our white neighbors and SeaTac”

…music…

There was pain here today. The now elderly children of incarcerated Japanese Americans remembered their loved ones lost, and the damage done to their families and communities. …And the still young children and wives of incarcerated migrants held by on the tall grey walls and barbed wire of the Northwest detention center remembered the faces of those they’d had taken from them.

There was also hope. Children folded paper cranes. Tsurus, in Japanese, a symbol for peace, compassion and hope. People played music beat drums, read poetry, chanted and remembered…Tsuru For solidarity is planning their largest action yet in Washington DC this June.

….music….

The violin you just heard was Kishi Bashi. I’m Sam Britt. Thanks to Yuko Kodama for help with editing.

Never Again Is Now Artwork to be featured at Bellevue College

Artist, Erin Shigaki, will be installing an art mural near the Bellevue College Main Campus Fountain today. The artwork is a wheatpaste of two children at a US government incarceration camp for people of Japanese descent during WWII.

Shigaki describes the art piece and why she chose this image for an installation.

Producer: Yuko Kodama

Photo: Purple Gate

Kishi Bashi – Omoiyari Album

Japanese American, Singer and Songwriter, Kishi Bashi’s (Kaoru Ishibashi) latest album, Omoiyari highlights the experiences of incarceration. The Japanese word, Omoiyari, means holding empathy and compassion. The album is the result of two years of Ishibashi’s numerous interviews with with those affected by, and visits to former WWII internment camps, where around 120,000 Japanese descendants across the United States were incarcerated.

KBCS caught up with Ishibashi before his Seattle performance at the Showbox SODO in early October.

Producer: Yuko Kodama

Photo: Max Ritter

Thanks to John Woodgate for transcription. Special thanks to Tamiko Nietering for assistance with this story.

Yuko Kodama 0:00

KBCS 91.3 I’m Yuko Kodama.

Kishi Bashi, is a singer and songwriter whose most recent album “Omoiyari” centers its lens on the experiences of about 120,000 Japanese descendants who were incarcerated in internment camps during the Second World War. Research for this album took Kishi Bashi, or Kaoru Ishibashi on numerous trips to visit former internment locations throughout the United States. He spoke with me about this experience at the Showbox Sodo in early October.

Unknown Speaker 0:35

Song

Yuko Kodama 0:50

Tell me about that first time that you went to Heart mountain and what that felt like for you as someone coming from a family that didn’t experience being incarcerated in the camps.

KB 1:04

That wasn’t the first place I went, actually I went to Manzanar and Poston first actually, and some of the West Coast sites like the assembly centers. And honestly, it was a little troubling at first. I went to Manzanar and I don’t know if you’ve been there, but it’s a beautiful place under the Sierra Nevada mountains. It’s very peaceful, you know, you go there and you’re wonder “why am I not feeling the trauma, or the injustice that happened” and I think you can’t feel bad about yourself for not being able to process things immediately. I think it sometimes it takes time might take years and maybe never, you know,

Yuko Kodama 1:35

As you’re talking about this, you know, you might have had a more difficult time processing it at first, but then you’ve come to work on music that is speaking to the processing of this and videos around this as well. So as you’ve been processing, where’s it taking you?

KB 1:54

I was writing music all throughout. Sometimes at the places sometimes just in hotel room or sometimes at home, after visiting and I think what that really did was to collect my ideas in to a musical form that I could compile later. I definitely have a larger view of what the conflict was like in World War Two ethnically and racially, you know, it was it was a complicated time.

Speaker 1 2:16

Tell me about some of the songs that you’ve worked on, speak to some of these concepts that you’ve been working through.

KB 2:23

Well, okay. Like, for example, I have a sample theme for Jerome, which I wrote for the Jerome incarceration center in Arkansas, which I visited. And what I didn’t really realize initially, was that the camps are really full of Japanese people. We like to say, Oh, they were Japanese Americans. And for the most part, they were Japanese people coming to America to make a better life for themselves. And obviously, their kids were naturalized, born in America and as American as anybody could be, right. But there’s so much Japanese culture in these camps, that a lot of it was suppressed. And a lot of times, parents from Japan, “Issei”, first generation parents, would make the difficult decision of suppressing their culture in order for their children to survive. And for me that was extremely painful because I value my Japanese heritage and I speak Japanese. It’s kind of heartbreaking for a parent to have to do that for their kids. And I think there’s probably some immigrant communities today in America that might feel similarly that they have to make this difficult decision to suppress their culture so that their kids can have a better shot at assimilating

Unknown Speaker 3:27

song

Speaker 1 4:00

Tell me about your daughter, you took her to Heart mountain? What made you decide on that? This is a personal journey for you where you took your parents and how was that? What brings you back to these places where people were formerly incarcerated over and over?

KB 4:17

I mean, honestly, it’s I think the people bring me back. You know, I’ve made a lot of friends in in Cody, and also people who attend heart mountain, the pilgrimage. For my daughter, it’s like, I want her to know what I’m working on. She knows everything about what I’m working on. Honestly, she’s likely will you stop talking about internment, you know, and I’d be like, “I wish I could”, but I talk to her about a lot of things and I’m convinced that her generation at least, you know, the people I see, are more empathetic, you know, and more ethical, I think, than I was when I was a kid. You know, to know that they’re okay with like LGBT and they’re actively trying to not be racist, you know, is is something that I, when I was 13 I didn’t I didn’t have any of that. Nobody was discussing racism. That much, you know, definitely nobody was gay, you know, they’re everyone’s in the closet, you know, back then. So I think like to see that it gives me a lot of hope and that when that whole generation becomes voting adults and taxpaying adults, it’ll be a different society. I also like to point out that a few years ago, over 50% of all school aged children are people of color. So that’s a very powerful indicator that this country is really headed into a more dynamic, diverse society that will have just only positive benefits, I think.

Unknown Speaker 5:43

song

Yuko Kodama 6:06

Next is part two of segments from a KBCS interview with singer and songwriter, Kishi, Bashi or Kaoru Ishibashi. Kishi Bashi shares his take on mass incarceration and racism with me at the Sodo showbox venue on October sixth.

KB 6:42

When I started to look into Japanese incarceration, there’s something that always was at the back of my head that I had to address which is like mass incarceration. The largest like ICE facility here in like Tacoma the detention facility, you know, Something that’s, I feel like every opportunity I get, you know, I need to mention it because it’s it’s such a problem. So “Angeline”, the song is about convict leasing, which is Jim Crow era, basically, criminality that was put on the African American people like especially males after the reconstruction after the Civil War, the South quickly just made up a bunch of the vagrancy laws to convict African Americans so that they could impose a fine upon them that they had to pay off through hard labor. So chain gangs, all those things, those are a result of convict leasing. And basically the foreman would come and the sheriff would round up people, and then just put them back on the plantations that they could have been formerly slaves on. Many considered it worse than slavery, because as a slave, you wouldn’t want them harmed, because they have to work for you, but as convicts, you could just work them to death. And so that’s the unfortunate story after the civil war that a lot of people still don’t really understand. We know the word Jim Crow, it’s in the textbooks, but the Legacy of Jim Crow and like lynching and all this stuff is still being uncovered. It’s a difficult topic for, especially for white people in the south to talk about, but it’s just something that needs to be continually acknowledged and talked about.

Unknown Speaker 8:19

Song

KB 8:39

African American males are viewed as criminals, you know, and this is why they end up in jail because it’s easier to put them in jail if you think they’re criminals, right? So it’s the kind of thing that I felt so strongly about, especially since I live in the south, I live in Georgia. There’s two camps in Arkansas. To see just this systemic racism that still exists there. It’s difficult to if you’re in a position of privilege to really acknowledge, but it’s just all around you. And if there’s so many communities that always live as second class citizens, you know, unfortunately.

Unknown Speaker 9:12

Song

KB 9:36

I mean, the most important thing about racism and discrimination, is that you just have to keep talking about it because it’s not like black or white or it’s a very nuanced thing for different people in different situations. So it’s literally evolving, dynamically, like every day, but it just needs to be talked about, you know, constantly.

Unknown Speaker 9:57

Song

KB 10:06

We’re all human beings with varying levels of fear and discomfort. Intergenerational the you can be a complete racist when you’re 18 and become a great part of society when you’re older. You know, people change.

I think we all have our preconceptions about what the world is supposed to be like. Every single person has a different perspective. They’re all like different universes. any random passer by has a world as vivid as your own. So you know, to have that in mind is a little humbling, but also makes it kind of exciting.

Unknown Speaker 11:30

Song

Yuko Kodama 11:35

That was music artist Kishi Bashi speaking with me in early October at the Showbox Sodo. 91.3 KBCS this is Yuko Kodama

How the Indigenous Community Assisted the Fort Sill Protest

Paul Tomita is a third generation Japanese American who attended a protest in June, against the Trump Administration’s plans to incarcerate 1400 children at US army post, Fort Sill this month. The organizers of the event were Japanese American, and some were elders who had experienced forced relocation and incarceration by the United States government during World War II.

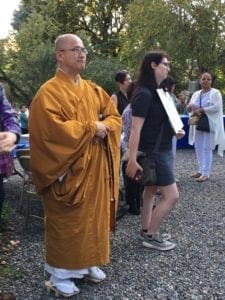

Lights for Liberty – Seattle Wisteria Park

The Japanese American Community organized a Lights for Liberty event on July 12, in Wisteria Park, across from the Seattle Buddhist Temple. This is a collage of sounds and impressions from people who attended.

Producers: Gol Hoghooghi and Yuko Kodama

Photos: Yuko Kodama

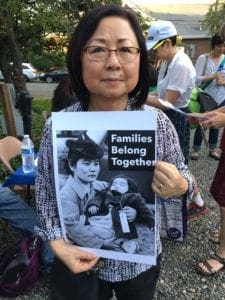

Alice Ito with a photo of her friend, Fumiko Hayashida and Hayashida’s daughter, Natalie on the day she left Bainbridge Island for the concentration camps in 1942. Hayashida was also pregnant at the time.

Attendees

Cranes on cyclone fence

Why Japanese American, Dr. Satsuki Ina Protests Concentration Camps at the Border

Over 700 Lights for Liberty events across the United States and in a couple of dozen countries were planned on Friday, July 12th, to protest concentration camps at the US southern border. Other significant protests within the past few months were one in Crystal Springs, Texas, and Fort Sill Oklahoma. These were both on or near sites where families of Japanese descent were incarcerated the United States government during WWII.

Dr. Satsuki Ina was one of the organizers for the Crystal Springs and Fort Sill events. Dr. Ina describes why she demonstrates against current United States policies of incarcerating people, families and children (separate from their families, at the southern border to Tom Ikeda of the Seattle-based, Densho Project.

From Hiroshima to Hope

“From Hiroshima to Hope” is an event commemorating the bombing of Hiroshima, Japan that occurred on August 6, 1945. The evening features musical performances, a Buddhist meditation, and floating lanterns on Seattle’s Green Lake. (more…)

The Black Panther Party – Seattle Chapter

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the Seattle chapter of the Black Panther Party. The Seattle chapter of the Black Panther Party was the first to be established outside of California. This series highlights some lesser known stories of Seattle’s local Black Panther Party.

KBCS’s Yuko Kodama speaks with Steve Roberson and Aaron Dixon, former members of Seattle’s Black Panther Party. Steve Roberson served as a vista volunteer for the Party in the free community health clinic and breakfast program in the early 70’s, and Aaron Dixon was the former leader of Seattle’s Black Panther Party.

Part 1 – Dixon explains how the Seattle chapter of the Black Panther Party was founded.Roberson shares about memories about the Black Panther Party health clinic in the late 1960’s.

Part 2 – Black Panther Party members were required to educate themselves about black history. The mission was to serve the community. Dixon describes a day in the life of a Black Panther Party member.

Part 3 – Dixon describes how the Black Panther Party free breakfast program worked and who donated to the organization.

Part 4 – One of the Black Panther Party’s programs was to protect the community from racial aggression. Dixon recounts an incident the orgnanization was involved in at Rainier Beach High School.

Part 5 – Roberson shares about an encounter at the Black Panther Party free community medical clinic that changed his perspective on community.

Part 6 – Dixon illustrates how the organization was supported by the local community during a confrontation with the Seattle Police, and explains the history behind a sculpture at Madrona Elementary school and Library

Part 7 – Dixon shares what happened as Black Panther Party chapters in Los Angeles and Chicago were attacked by federal government entities, resulting in 4 political assassinations of Black Panther Party leaders

Part 8 – Dixon reflects on how the Seattle chapter of the Black Panther Party weathered the more intense period after J Edgar Hoover proclaimed the Black Panther Party breakfast program a threat to national security.

Part 9 – Dixon describes how former Seattle Mayor Wes Uhlman stepped in to keep the local chapter safe.

Part 10 – Dixon gives his take on how civil rights and black liberation movements of the 60s and 70’s compare to the social movements of today.

Part 11 – Dixon shares the Seattle Black Panther Party’s relationship with Jimi Hendrix.